Thoughts on an Antifascist RPG, Part 2

(Read part 1 here.)

In the early 1980s, a college-age programmer named Richard Garriott—who’d written and sold his first computer game, Akalabeth, as a teenager—had established a successful series of roleplaying games for the Apple II computer, but as he looked back on Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness, Ultima II: The Revenge of the Enchantress and Ultima III: Exodus, he felt some ambivalence. Like many players these days, he had qualms about the fact that the games seemed to reward indiscriminate killing and looting. Thus, when he created the next game in the series, Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar, he took a different tack. He wrote a game that rewarded moral acts and punished immoral ones, that not only encouraged but required the player to refine the protagonist into an exemplar of virtue in order to reach the game’s conclusion.

In doing so, he also gave me the first explicit moral code I ever tried to live by.

At the start of Ultima IV, the player character protagonist encounters a fortune teller in a vardo who lays out a series of oracle cards, each pair presenting a moral dilemma, such as, “Entrusted to deliver an uncounted purse of gold, thou dost meet a poor beggar. Dost thou: Give the beggar a coin, knowing it won't be missed | Deliver the gold knowing the trust in thee was well-placed?” The first answer shows that you value compassion over honesty; the second, honesty over compassion. The game asks seven questions, with the first four chosen at random and the last three dependent on the answers to the first four, elimination bracket–style. Your answer to the final question, which establishes the virtue you hold highest of all, determines your character class in the game.

The eight “virtues of the Avatar” are generated from three fundamental principles: truth, love and courage. (In coming up with these principles, Garriott was inspired in part by the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodsman and the Cowardly Lion of The Wizard of Oz!) A commitment to truth alone produces the virtue of honesty, love alone produces the virtue of compassion, and courage alone produces the virtue of valor. Justice is the combination of truth and love, honor is truth plus courage, sacrifice is love plus courage, and spirituality is the combination of all three. Underlying them all is humility, the root of virtue and the antithesis of the anti-virtue of pride.

If you choose honesty over other virtues three times in answer to the fortune teller’s questions, you become a mage. Choosing compassion makes you a bard, valor makes you a fighter, justice makes you a druid, honor makes you a paladin, sacrifice makes you a tinker (a trap disarmer who can also repair broken gear), and spirituality makes you a ranger (there’s no cleric class in the game). Choosing humility above all makes you a shepherd—a mundane class that can wear only light armor and wield only simple weapons such as staffs and slings. Over the course of the game you gain a companion of each other class, but you yourself must ultimately demonstrate mastery of all eight virtues in order to complete the final task of the game: retrieving the Codex of Ultimate Wisdom from a dungeon and standing as an exemplar of virtue for all.

Others have their own explanations, I’m sure, but I believe that we’ve stumbled down our current path in large part because our own civic virtues have been neglected. Our education system devalues social studies in favor of superficial reading and STEM, and for my entire adult life, our ostensibly pro-democracy Democratic Party, faintly embarrassed by any expression that might be mistaken for patriotism, has utterly failed to defend the principles of equality, human rights and self-determination in any articulate way. In the absence of a shared commitment to democratic values, fortified by frequent and regular reminders of their importance, proponents of antidemocratic values rush in to fill the void … and here we are. At this point, I can’t see any path out of fascist insanity that doesn’t involve loudly and repeatedly emphasizing the essential truth summed up in article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act toward one another in a spirit of brotherhood.” (If “brotherhood” strikes you as outdated and sexist, substitute “kinship.”)

While musing about possible mechanics for an antifascist tabletop RPG, in which brute force must be opposed by means other than brute force, I recalled Ultima IV and its schema of virtues. Truth, love and courage: There’s power in those principles. They’re the rejoinder to the lies, cruelty and intimidation that form the core of fascism, and the antidote to the ignorance, numbness and fear that fascism begets.

Let’s make that the foundation of this hypothetical game. Somehow, the PCs will resist a fascist regime by harnessing the power of truth, love and courage. Genre doesn’t matter much: It can be high fantasy, low fantasy, modern fantasy, science fiction, cyberpunk, solarpunk, alternative history, whatever. It might be more fun, though, to include fantastical aspects rather than risk its turning into a textbook on real-life resistance. If we want to play that game, we can go outside.

Now let’s think about how truth, love and courage function in this game we’re imagining:

- Truth disrupts the tyrant’s ability to dictate orthodoxy. It challenges the tyrant with a counternarrative that reveals the moral hollowness of the regime. It reveals facts to people that they’ve been denied access to.

- Love offers protection and kinship to others. It restores health, eases pain, forges bonds and allows happiness to take root. It is mettā.

- Courage defies the power of the oppressor. It sees what’s right and does it, heedless of danger or cost. It refuses to comply in advance—or at all—with illegal and inhumane orders. It says, “My will is as strong as yours. You have no power over me.”

As a recently minted folk hero might put it: Dispute, Defend, Defy.

Next, let’s distance ourselves from the traditional classes of Dungeons & Dragons and other fantasy RPGs. Let’s instead imagine classes that harness the powers of these principles in setting-specific ways—magical ways. Anyone can be an organizer, but let’s suppose that the PCs have special abilities that empower them beyond what a normal person can do, rooted in their own paramount virtues.

- Truth: Honesty. Adherence to the facts. The Soothsayer sees through lies and can compel others to speak the truth.

- Love: Compassion. Sympathetic consciousness of others’ distress, together with a desire to alleviate it. The Heartkindler dissolves hatred and can compel others to see victims’ humanity and feel their suffering.

- Courage: Valor. Strength of mind or spirit that enables one to encounter danger with firmness; personal bravery. The Rebel restores and bolsters the confidence of the oppressed and undermines the confidence of the oppressor, turning the tables. This doesn’t necessarily make the Rebel (or others) any stronger physically, but it weakens the resolve of those who’d attack or abuse them (or others).

- Truth + Love: Justice. Maintenance or administration of what is right and proper, especially by the impartial adjustment of conflicting claims or the assignment of merited rewards or punishments. The Rectifier holds power to account for its abuses and renders restitution and restoration.

- Truth + Courage: Honor. Good name or public esteem; merited respect; a keen sense of ethical conduct; integrity. The Oathbinder reveals truth and falsehood through public acts of defiance, shaming the shameless and making others fear to lie or break their word.

- Love + Courage: Sacrifice. Destruction or surrender of something for the sake of something else. The Propitiator gives their own resources to others, increasing the quantity of those resources in the process. Propitiators can offer themselves as substitute targets of harm, an act that emboldens bystanders.

- Truth + Love + Courage: Spirituality. Concern with sacred matters. The Thaumaturge turns others’ attention to higher truths. They have access to the kind of divine magic otherwise monopolized by the church-state. A Thaumaturge is a heretic with power, a nucleus of revolutionary inspiration.

- Ø: Humility. Freedom from pride or arrogance; the quality or state of being insignificant or unpretentious. The Cipher is unacknowledged and overlooked, able to go anywhere without drawing attention.

I’ve already discussed how I think D&D, Pathfinder, the Cypher System and Blades in the Dark are ill-suited to a game like the one I’m imagining, but one TTRPG system I haven’t discussed, which I think might actually be suited to it very well, is Cortex Prime. In this system, Truth, Love and Courage would constitute a Values trait set. Soothsayers, Heartkindlers and Rebels might each have one trait rated 12 and two rated 6; Rectifiers, Oathbinders and Propitiators might each have two traits rated 10 and one rated 4; Thaumaturges might have all three traits rated 8; and Ciphers might have all three rated 6, plus something special to compensate. The remainder of the trait set might consist of Distinctions and Roles, Distinctions and Skills or Distinctions and Affiliations.

Research into bullying in schools and other social groups sorts participants into various roles: the bully and the victim, of course, but also henchmen (followers who assist or reinforce bullies), bystanders (who look on passively) and defenders (who stand up for the victims). According to the research, bullies can’t really be removed from the bullying role except by withdrawing the support structure that allows them to take advantage of their victims. This withdrawal of support is accomplished by turning henchmen into bystanders and, importantly, turning bystanders into defenders.

Fascists are bullies with social, political and governmental power. They thrive on the helplessness of victims, the passivity of bystanders and the obedience of their supporters. Most of all, they thrive in the absence of defenders. Thus, “quests” in an antifascist TTRPG are primarily about undermining the conditions in which fascists thrive and sapping the sense of inevitability and invincibility they seek to create. They involve making henchmen hesitate to obey, activating bystanders, providing aid and comfort to victims and making the bullies themselves appear ridiculous, petty and weak. Thus, this hypothetical game, and the PC classes described above, are all conceived with one end goal in mind: to generate an ungovernable groundswell in support of civic virtues that the regime can no longer stand against.

That, I think, is what would make a game the quintessential antifascist TTRPG.

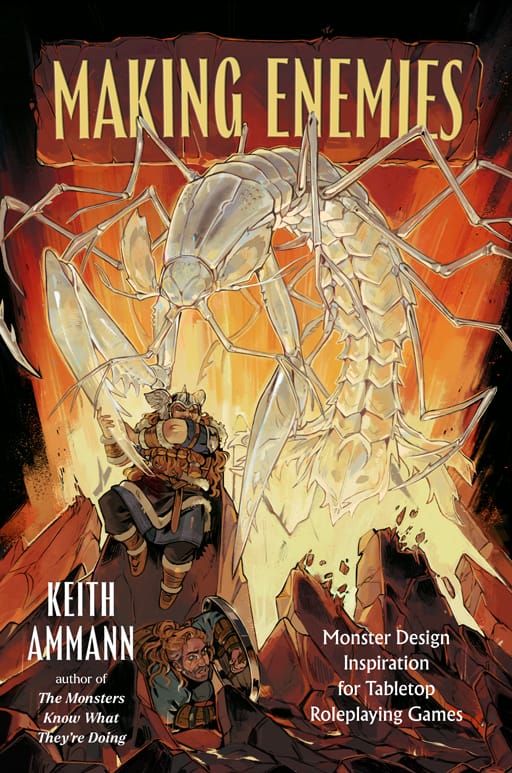

In The Monsters Know What They’re Doing, the essential tactics guide for Dungeon Masters, and its sequel, MOAR! Monsters Know What They’re Doing, I reverse-engineered hundreds of fifth edition D&D monsters to help DMs prepare battle plans for combat encounters before their game sessions. Now, in Making Enemies: Monster Design Inspiration for Tabletop Roleplaying Games, I explore everything that goes into creating monsters from the ground up: size, number, and level of challenge; monster habitats; monster motivations; monsters as metaphors; monsters and magic; the monstrous anatomy possessed by real-world organisms; and how to customize monsters for your own tabletop roleplaying game adventuring party to confront. No longer limited to one game system, Making Enemies shows you how to build out your creations not just for D&D 5E but also for Pathfinder 2E, Shadowdark, the Cypher System, and Call of Cthulhu 7E. Including interviews with some of the most brilliant names in RPG and creature design, Making Enemies will give you the tools to surprise and delight your players—and terrify their characters—again and again.

Preorder today from your favorite independent bookseller, or click one of these links:

Spy & Owl Bookshop (hi it me) | Barnes & Noble | Indigo | Kobo | Apple Books